In Conversation with David Dawson: An Interview on the Studio Practice of Lucian Freud

ENTERING THE STUDIO; ENCOUNTER AND INTIMACY

Joshua Press: Do you remember your first experience sitting for Lucian – the feeling you had first seeing your likeness on the canvas? How early was that into your working relationship?

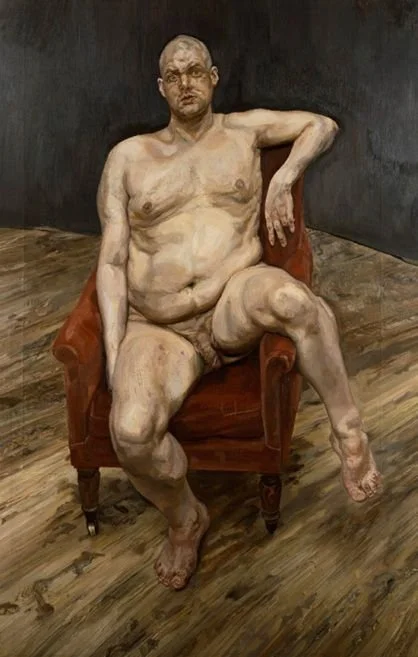

David Dawson: I think the most important moment was when I first walked into the studio. That had a bigger impact on me than sitting. A different impact, profoundly more moving. I’d met Lucian a couple of times in Holland Park, and one morning he said: ‘Come into the studio with me.’ That was about two weeks after I’d met him, and I walked in, and right in front of me was this big easel with a half-finished portrait – the first big portrait of Leigh Bowery.

That was so moving, seeing someone working as hard as he could to make the best quality painting he possibly could. It had a really strong effect on me. I just felt something really serious was going on, and it absolutely mesmerised me. It was purely visual – the painting really took hold of you.

That was my very first encounter with the studio, and it still holds a very strong, palpable sort of feeling for me. And then, six years on, he just said one morning: ‘Oh, I’ve got an idea for a painting – will you sit?’ I was very excited by that. Because it was a big painting, it meant I could see what he was doing.

At first you’re a little bit shy and a little bit nervous, even though I’d known him for six years by then.

You don’t quite know what you’re meant to do, and Lucian doesn’t direct you in any way. My only question was whether I should be clothed or unclothed, and he said: ‘Clothes off’.

So you take your clothes off, and you feel slightly self-conscious for a little bit, but not really, because you know you’re there for a purpose.

Then you lie in the bed and work it out for yourself – how you’re going to lie. Lucian doesn’t want to direct you in any sense. You’ve got to find out for yourself how you sit. It’s very much you showing him what you’re like. You have a few goes at it, and some things work and some things don’t. And then, as the painting develops, it slowly gels into the position you will hold for many months.

Joshua: Would Lucian suggest a certain pose to begin with?

David: He’d have the idea, like, ‘just go and lie on the bed’. But it’s your choice, how you lie down, and that’s very telling I think – you make the decisions.

Joshua: There would be an initial pose, and maybe for the purposes of the composition, or for comfort, the pose would change?

David: Comfort didn’t come into it. For the picture, an arm might get raised, or dropped, or a leg might get pushed across. After a few goes, you might be slightly moving around, and then Lucian would just say, ‘hold it’, without any explanation of why that works. That’s one of the things with Lucian’s paintings: it sort of remains private. There are no answers in there, and yet he will stop you at one point and go: ‘Oh, that’s the pose, just hold that’. You don’t know why – there is no explanation – but it works for him. And, slowly, he works in a very small area of the canvas and builds it through.

Maybe it starts around your head or a shoulder – he’ll build that up until it’s almost complete, and then that spreads. It’s about how limbs attach to other limbs, how bodies are formed, how bodies are made. That’s why it helps having your clothes off. It gives more of yourself because you’re naked and feel more vulnerable, and it shows him your psychology – not just the physiology of how you’re put together.

That was important for Lucian as an artist. I really think it’s about your behaviour, what he was painting – human behaviour. I think that’s what Francis Bacon was painting as well. It’s how an individual behaves…

Joshua: …expressed through form.

David: Yes, and how you sit there, lie there – with your energy around you. When he spoke about the air around you, he was always very sensitive. He could feel different people’s – that awful word – ‘aura’.

Joshua: Do you think there was a metaphysical element that came through with such a penetrating gaze?

David: Exactly – and just how you hold yourself. That’s very telling.

Joshua: Was that intimidating?

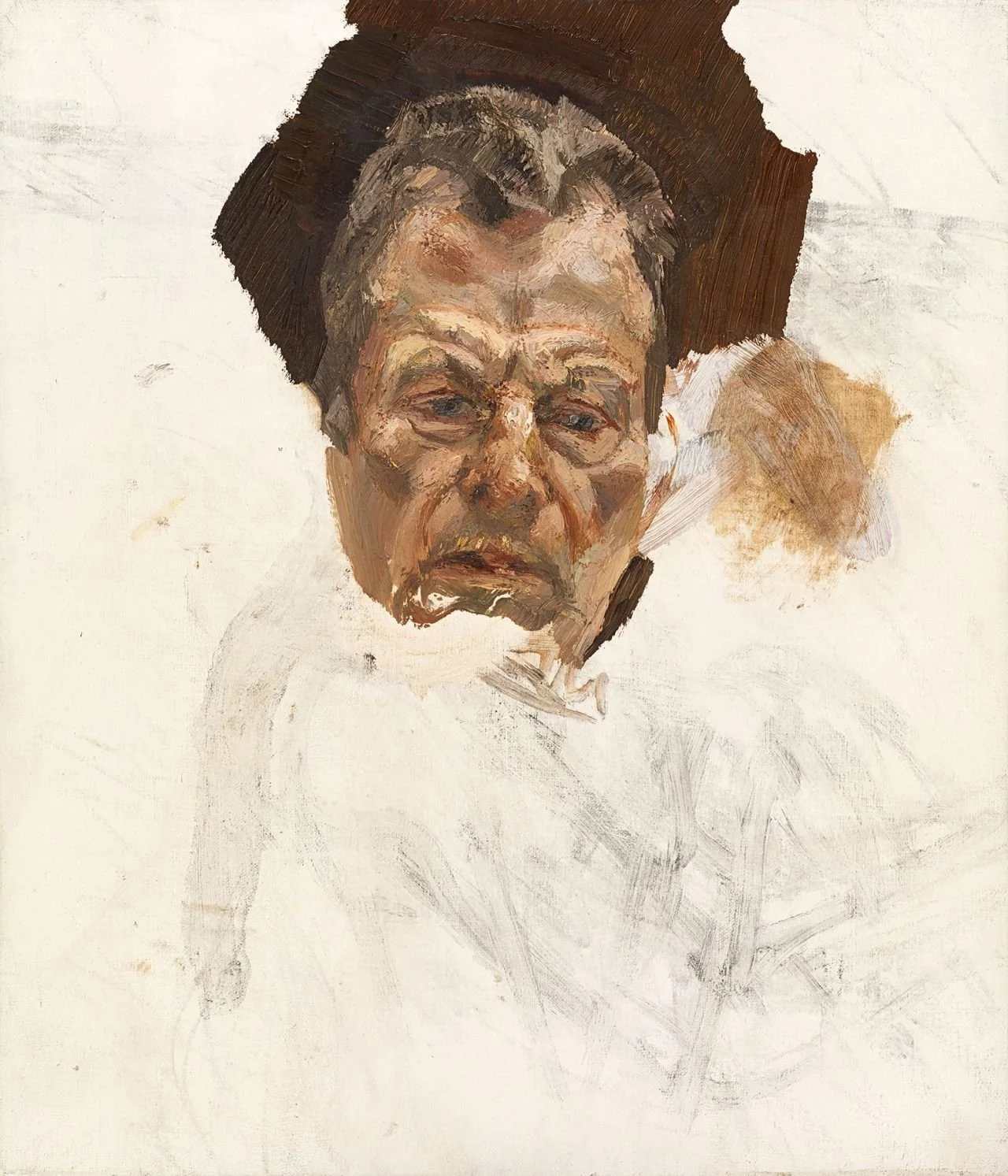

David: Never intimidating, but you give yourself over to him. There were no games – it goes on too long to play mind games. You can’t be silly. The paintings always take a year or two. You can’t keep up any pretence. A sort of watchful understanding of you develops. That’s what makes great portraiture. I think that’s what people are fascinated by when they look at these paintings –he puts an inner life into the portraits.

Joshua: Which comes from that scrutiny of observation?

David: Yes, but also his intelligence. I think that’s what he brought to portraiture in a new way – the inner life of each person. Right from his early work, the fine early portraits of his second wife, Caroline – the very early, thinly painted portraits, when Herbert Read called him ‘the Ingres of existentialism’. It’s a good quote, because each of those portraits gives you something else. That’s what he brought to portraiture, I think: this ‘inner self’. And also, with those portraits, you’re really close to them. I mean, he’d come up very close to you when he was painting, and that closeness carries through to the finished canvases. When you look at them, you’re immediately in a very intimate space with that person. I really enjoy seeing people looking at those paintings in a public museum. They spend a long time – they don’t just look for a few seconds and then move on to the next one. I think it’s because that painted head brings you into a really intimate space with that person, even though you might not realise it.

Joshua: All those accumulated moments condensed into one experience.

David: Exactly.

COLOUR, SCALE, STARTING AGAIN

Joshua: Which colours were on his palette? Did they ever change in relation to specific subject matter – like a strongly coloured fabric?

David: Well, Lucian was 69 when I met him, so he would have had 40 years of painting. He knew his colours. He had a big range, and they were always pretty much the same. But yes, for certain fabrics you would bring in something different – the cadmium red might come in, for example. My basic shop was always: Naples yellow, Naples yellow pale, Naples yellow dark. Cremnitz white for skin. Flake white for inanimate objects – he never used titanium, it was far too strong for him, too glary. Flake white is very soft. All the umbers: raw umber, burnt umber, raw sienna, burnt sienna. Ultramarine, cerulean… He never used Prussian blue – that was far too strong.

Joshua: Cobalt?

David: No, not really… charcoal grey, Payne’s grey, lamp black, cadmium red, alizarin crimson, transparent red oxide and terre verte, the cadmium yellows – Indian yellow was a big favourite. That’s pretty much it.

Joshua: Quite a broad palette.

David: He did have a broad chosen group of colours. Oh, and there was a Blockx, which is a Dutch company, isn’t it? There was a yellow, a very cold yellow…

Joshua: A lot of yellows!

David: Yes, but he’d never use any straight from the tube. Each one was mixed. Whereas Frank Auerbach would have a massive tub of red, yellow, blue, and they could go almost directly on the canvas.

Joshua: Did the mixing happen with a knife?

David: The mixing would happen on a handheld palette. He would mix with a knife: make one or two brush strokes with a colour, scrape it off and do it again.

Joshua: Is that how the sessions would tend to start – by finding out what was happening, in terms of colour?

David: Yes, but he would make one colour each time, put one or two brush marks down, then clean that and start another colour mix. He didn’t have a range of colours to dip into.

Joshua: Just exploring how the harmonies worked?

David: I think that taking a long time helped him think and decide what marks to make.

Joshua: Did the duration of the paintings vary much? They’re known for requiring many sittings from their subjects, but were there paintings that were resolved noticeably quicker (or slower) than others? Would a smaller work move faster than a larger one?

David: Scale did play a part, but the small pieces still took 12 months. Lucian would never do anything less than that. Some things would go really well early on, and there are one or two paintings out in the world which aren’t completely resolved – the canvas is still bare. Those ones were going so well that he’d just let them be. That happened a bit, but for every painting that’s come through, there would be three or four attempts that he would start and then abandon.

Joshua: On the same canvas?

David: No – there was always a big pile of canvases ready. He’d always have three or four goes. Not every time, but it wasn’t uncommon. And if he went on to another canvas, I’d be the one to decide whether or not to destroy the old one or keep it. I’d have that conversation with him. Most of them would be destroyed.

Joshua: Would he often abandon canvases that were already quite developed?

David: Sometimes, yes. I remember one with this girl he painted. I thought it looked really good, and just about finished. And then he said: ‘It’s not good enough’, and put a knife through it. The girl had sat for 18 months.

Joshua: Did they start again?

David: No.

Joshua: How would the models be affected by that? Were they always willing to keep going?

David: It was hurtful. Lucian didn’t want to stop like that. It would demoralise him – never mind demoralise the model. He didn’t want that to happen too often, but it did happen once or twice.

PRACTICE AND PROCESS

Joshua: Did the struggle involved in producing particular works affect Lucian’s mood? Did he ever discuss that struggle with you, and the truths he was striving to understand?

David: He never really discussed his painting in a direct way. He would allude to it in other rather brilliant ways – through another painting at the National Gallery, or through a poem – but he was incredibly tense about his work, always. He never relaxed. He was very contained. But as I knew him more and more, I could tell the underlying currents. You could tell when things were really tense. And every day, when he got to his easel, it was tense.

Joshua: There was always that kind of pressure, self-discipline, always striving for something better?

David: He didn’t sit back and let it roll.

Joshua: But in the midst of all that, he was jovial?

David: Yes! Very good company. I think that was another part of his extraordinary portraits – he was really good company, so people came back to him. People wanted to be around him. And he didn’t feel any pressure from always asking someone to come back for two years, four times a week. It didn’t affect him.

Joshua: He wasn’t scared that they might not show?

David: Well, he carefully picked people who stood a good chance of not bailing out halfway through. That would really fuck him up.

Joshua: That must have happened?

David: Not often. Maybe when he was younger, but not when I was with him. Once or twice. It was more if he was caught up in a in a very intimate relationship with a girl, because that had a different effect on the paintings.

Joshua: Life could get in the way.

David: Yes, but his life was painting. I’ve never seen another artist work as hard as Lucian. I mean, Hockney works hard… but Lucian would get up early and start and the sitter would arrive at eight in the morning and sit until lunchtime. Then there would be another sitter from six in the evening until midnight, seven days a week, every single day of the year. He thought that every time you go to bed and wake up the next morning you’re like a different person, and when he was younger I think he really hated that. It threw him out. One way of trying to control that a bit is to paint non-stop: all day, every day. Rather than lose yourself.

Joshua: And there was never any lapse in that?

David: Never, no – not when I knew him. I mean, when he was younger, there was a bit more running around.

Joshua: So 25 years, seven days a week?

David: Yes.

Joshua: That’s incredible.

David: It’s because he absolutely put painting first, always.

Joshua: Do you think there’s anything to which he could attribute that sort of consistency? To an individual inspiring him?

David: Very early, he told me that Cedric Morris played a big part when he was 16 or 17, at Benton End, allowing him to be free as an artist and not be caught up in rules. As soon as there was a rule, Lucian would want to break it, so this sense of a sort of bohemian life and freedom allowed him to paint. That really got him going. And he said that to get ahead, you’ve really got to concentrate and be better than anyone else. He was very aware of that. He learned that at 16, and it never left him.

Joshua: No holidays or anything like that?

David: When he was younger he would run around.

Joshua: But not in his later life.

David: No. I mean, he had a good life, with one or two very close friends. It was very civilised.

Joshua: Obviously Auerbach is known for that as well.

David: I remember seeing that really good show that Gagosian did a couple of years ago of Auerbach, Bacon, Lucian and Mike Andrews, and I really felt like it was another era. That era’s gone. Those guys really took painting seriously and pushed as hard as they could.

Joshua: They set the bar very high.

David: I think so. I think they really stood out. And I felt: ‘God, that’s quite extraordinary, what they all did’.

Joshua: Lucian was known to start each work differently, and rejected the notion of formulas or methods. Was there any consistency to his process at all? When starting a painting, did he favour colour over drawing, for example? You suggested already that he would pick a meeting of forms and let the painting develop from there.

David: There would be a very loose charcoal underdrawing, just to get an idea of where the body was going to sit in the canvas, done very, very quickly. Trying to get things in the right place. And then that would be rubbed off, so there’d be a ghost image of it, and then you start. Then, when you start with the paint, things grow. In the later years especially, the canvases would quite often be extended because he never wanted the shape of the canvas to limit the forms – he wanted to allow them to develop. And if that meant the foot was going further and further, then you’d add more canvas.

Joshua: There are a few compositions when he does abruptly crop forms, quite beautifully.

David: That’s very deliberate. Everything about his painting is very deliberate. It might not look like that – the floorboards recede, and then there’s part of a wall – yet it’s all constructed, and it all works to make the painting come alive. It’s not exactly how it is – it’s his own invention as well.

Joshua: That’s something that can be quite hard to fathom about figurative paintings, because they can be so convincing as metaphors for life. It’s just incredible how much intent was within those canvases.

David: The intent is what is more striking than anything. Most people, it they worked on a painting for a couple of years, would kill it. Somehow Lucian brought them through.

Joshua: It’s probably to do with that consistency.

David: It was just how he found his way of working. He always said that Bacon almost lived on inspiration. Painted on inspiration. Lucian thought that when Bacon was good, he was the most marvellous artist ever. And it’s that sort of accidental intent, with the brush mark and flick of paint… for Bacon, it can really hold something. Lucian had to work out for himself how he was going to do it.

Joshua: That strange combination of absolute focus and attention, but also somehow of intuition…

David: Intelligence, an intelligence is what shines through.

NIGHTTIME IN THE GALLERY

Joshua: Copying is something most painters investigate at one time or another. Degas famously said: ‘The Masters must be copied over and over again, and it is only after proving yourself a good copyist that you should reasonably be permitted to draw a radish from nature’. Lucian made a beautiful copy of the Chardin at the National Gallery. Could you tell us anything about that particular work and how it came to be?

David: Lucian would never say it was a copy, but a reinvention. He was making his own painting about the painting. So it’s not a copy. It’s something else. He thought anything Chardin did was absolutely marvellous – how Chardin used his paint. I’d go to the gallery with him and he’d paint in front of the painting. We would leave the paints and easel there.

Joshua: Was that a daily thing?

David: A nightly thing. Not every night, but it went on for a while, because he did two paintings and two etchings. They were all done on site.

Joshua: So it probably went on for over a year?

David: Oh yes. One of the paintings is very small, six by eight inches, and it’s really cropped in on the child’s head and the schoolteacher. But even though it’s only that size, the heads are a similar size to the Chardin. The larger painting is just a couple of inches smaller. Again, Lucian has chosen to bring the figures a bit closer. He hasn’t put the pen into her hand. He’s made slight changes that suit his painting.

Joshua: This was all happening after the opening hours?

David: Yes – we’d go in at around seven or eight and come out at one in the morning. That was amazing, because I was always with him, and I’d just go around the National Gallery. That’s how I got to know the collection. You just relax into it and daydream. You don’t have to go in there thinking: ‘I’ve got to go and look at the painting’. You just go and sit on those wonderful, big settee things and just hang out on your own with the paintings. That’s how I built up my own relationship with the National Gallery. It was just being there with Lucian. It was brilliant.

Joshua: How did that work, logistically? Was there a pass for certain artists so that they could access the gallery?

David: There’s a 24-hour pass that trustees have, and Lucian had one. You just phone up and say: ‘I’m coming in’. The security are already there – they have to be. They just know you’re coming in, and you can do your thing. The lights go on for the rooms you need to be in. There are lots of little school rooms off the main rooms, so you can just pop your easel and paint in there. It was 1999 and I can’t remember if we could still park outside then, or whether or not it had been pedestrianised – because at one point you could just park up right outside the gallery and walk straight in. The painting after Chardin was because the gallery was putting on an exhibition called ‘Encounters: New Art from Old’ – so that painting was done with that in mind. Back in 1987 there had been an exhibition in a series called ‘The Artist’s Eye’, where they’d asked artists to pick paintings from the collection, and Lucian had picked the same painting.

Joshua: He helped curate that?

David: It was his choice of paintings from the collection that he thought most pertinent to him. There were seven Rembrandts, three Degas, three Constable, two Frans Hals, two Ingres, a Velasquez, a Rubens and a Chardin. That was Lucian’s choice for ‘The Artist’s Eye’. It was a good show! He thought anything that Chardin did was just so brilliant. The human presence in the Chardin is utterly believable. Courbet was another artist Lucian really rated.

Joshua: Do you know which paintings?

David: The two girls lying beside the Seine – that was very much in his painting. You can see how they then translate into the paintings of couples that Lucian has done. He also thought Constable’s portraits were fantastic. He curated a show of Constable portraits at the Petit Palais. It brought prominence to Constable’s portraiture.

Joshua: Did Lucian speak much of his pictorial influences in the studio?

David: Well, he’d always have a book lying open, just to give you that glimpse of brilliance.

Joshua: But influence was not necessarily overtly discussed?

David: Well, there was the ‘After Watteau’ painting, which was very much about a particular painting.

Joshua: Would he describe the particular elements he was chasing?

David: If asked. No more than usual. He wouldn’t underline the point. It’s a quality in the work, things that just surprise you and make you feel alive. Art always comes out of art. He had a deep understanding of paintings – not in an academic sense, but a real understanding of what the intention of the artist was and how they made it come alive. On the whole, it was a northern inspiration. He was influenced by Rembrandt and a northern sensibility. But, saying that, Titian and Velasquez were important too.

Joshua: More so (LF’s Northern influence) than Titian and Velasquez?

David: No, not more so, but as much. He wasn’t going into high Catholicism or anything like that.

DRAWING, TRAINING, CONTEMPORARY ART

Joshua: Lucian produced a lot of beautiful drawings and works on paper. But with such a prolific painting practice – as you said earlier, every day, all day long – how did drawing find its way in? When would the sketchbook come out?

David: Drawing wasn’t really a big part of his daily work in his later years. There would be occasional drawings that would come through, but not many. He started off drawing when he was really young, and got known for it when he was in his teenage years – making rather extraordinary works on paper. And the illustrative work, book illustrations and poems.

Joshua: There is one very beautiful pencil drawing of yourself. When did that happen?

David: He did have sketchbooks lying around the house, and he would just pick one up. All the sketches went to the National Portrait Gallery – there was no chronological order to them. He took the quality of paper very seriously, he valued it. He liked the individuality of everything and the particularity of everything, so the paper tended to be very fine French paper.

Joshua: Would the drawings happen in midst of the sittings, or were they just happen around the house? Would they take place in the studio?

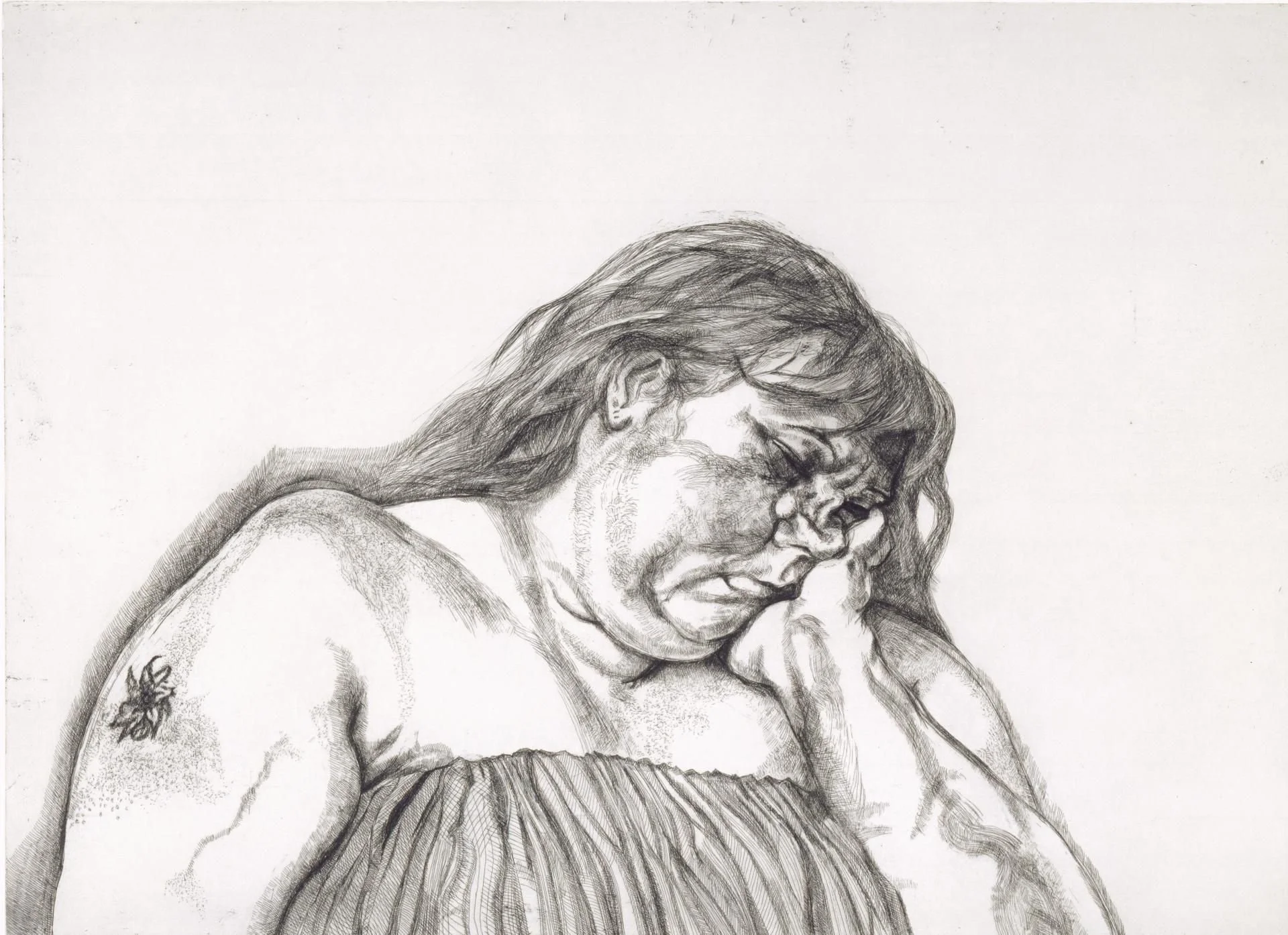

David: They just sort of happened. More consistent in my time were etchings. After a big painting, he would always do an etching,

Joshua: Continue with the model, and make an etching afterwards?

David: He felt he knew the model so well. So the etchings always came after a portrait.

Joshua: So the drawings were a little bit more sporadic?

David: Yes, when I was around. There’s the etching of big Sue, but that came about because she had a suntan. Things like that would result in a drawing or etching.

Joshua: Art education changed drastically in Lucian’s lifetime, with a departure from tradition, and a decreased focus on drawing from the nude and direct observation. Did Lucian ever share his opinion on this with you?

David: Well, Lucian never believed in academia. He thought that it was second hand. His attempt at being in Central Saint Martins – which was more of a traditional art school back then – didn’t go well. That’s when he went to Cedric Morris, a much freer environment.

Joshua: These days even that might be considered academic to a certain degree – students putting a lot of effort into drawing the world around them.

David: To a certain degree, yes. Lucian always believed in finding out for yourself.

Joshua: At the same time that he was making such profound paintings, there was a big shift happening outside of his studio, with the YBAs and more conceptual work coming through. I wonder if he had any thoughts about that, or if he’d just let people get on with it.

David: He did have an interest in it, but it didn’t affect his own work, or how he made work. In his 50s and 60s he lived next-door to Richard Hamilton, who said to him: ‘Why are you bothering doing this old-fashioned stuff – you know, all this brown paint?’ Lucian really liked that reaction – that people really disliked his work. It gave him the freedom to let them get on with all the fuss and the hype, and he could be anonymous and get on with what he wanted to do.

Joshua: Do you think he ever thought about posterity, in the sense of whether people would draw from observation, or paint from life, in the future? Did he ever think about artists coming through?

David: He thought that you gave yourself a better chance of making great art by finding something that affected you, and if that was through observation, then that was it.

Joshua: He wasn’t necessarily bothered that it was out of fashion?

David: No. He just did what he wanted to do. He thought that was how you gave yourself the best chance of doing something worth doing. Everyone has to find their own way, don’t they? Lucian had to have the sitter there, even when he was painting the air around you, or the table over there – you had to be there to correspond with it. Frank Auerbach would draw outside in Camden, and then work on the paintings from the drawings, which weren’t scribbles, but they were a shorthand for what he wanted. Francis Bacon used photographs. Everyone has to find their own language. Lucian never found any interest in photographs because they’re already two-dimensional flat images. He said they’re abstract – there’s no point in looking at photos.

Joshua: They never came into the studio?

David: No. There were one or two very small paintings with a sort of photographic base, but they had no potency for Lucian. Whereas that’s what Bacon wanted to work from – he didn’t want the person in the room. He could get what he wanted out of seeing all these photographs lying on the floor. Hockney paints from a sitter at the moment, but years back he used photographs.

Joshua: I wonder what Lucian would make of figurative work being done today. There’s been a second wave of figuration recently, yet the work is in a very different vein to his own.

David: He always wanted to see what was going on. He was petty damning, but in a way that was witty. He’d absolutely undercut everything and slam things…

Joshua: I can imagine that!

David: …but his main interest, and what occupied his mind, was his own work. I think many of the great artists need that sense of self-worth – and self-obsession – to keep the work going. So he would look at stuff and he’d dismiss most of it. That’s why we would always go to the National Gallery – we’d never really go to the Tate. As he said, every time you walk into the National Gallery, you always come out feeling better. He just had very clear insightful answers to what he liked and what he didn’t think was worth bothering with.

DAVID DAWSON’S OWN WORK

Joshua: Having spent so much time working closely with Lucian, did any particular aspects of his painting inform your own? Firstly from a pictorial perspective, and secondly in terms of materials and the way you light your studio, for example.

David: I think I really learned: apply yourself and believe that the marks you make are worth keeping. Also, keep alive the delicacy of the surface of the canvas. Don’t kill anything. Once you kill something, it’s very hard to revive it. That’s a big learning curve. Really it was just the application and approach to the job in hand: painting. Finding what it is that really excites you, and digging deep. I think I learned what quality is. When we started the conversation, I was trying to explain the feeling when I walked into his studio and saw this painting for the first time. The quality was so high. I’d only just come out of the Royal College, where everybody was looking at New York painters. It was a very different education. And to see what Lucian was doing… it was serious. ‘Original’ is such a clichéd word, but it was singular, and it moved me. It moved me in a contemporary way. I thought: that’s what art is. Not the hustle and bustle of New York. I mean, that’s also part of our life, the hustle and bustle of urban living. But what Lucian was doing was serious and yet so impactful. It would change you.

Joshua: It’s quite amazing that the first visit is what really remains.

David: Well, it was epic, to enter a studio to see the first one of Leigh Bowery coming out. It was charged. That’s why I hung around. That was one of the best paintings he ever did, and to see that halfway through, it meant something to me that was real. It wasn’t a contrived art world experience, it was like: ‘Oh my god, this is what art is’.

Joshua: Is that something you can ever get used to? The paintings of that period were particularly powerful, in the context of his body of work. Those paintings are loaded.

David: Well, he was just about to hit 70. Bacon was at the end of his life, or might even have just died. So Lucian was aware of his standing as an artist, and he had to push himself. He went into very ambitious, very large canvases.

Joshua: From your perspective, did you get used to that kind of quality, that sort of focus?

David: No. I knew he was at the top of his game. It was exciting, because I could see all my mates from the Royal College – from the same year as all the YBA’s – and I was watching what they were doing, and I just hung out with Lucian. London was good in the 90s. Lucian knew what he wanted, what art could be, and he was going for it. It was an amazing period to watch him his full stride. It was special.

Edited by David AndersonDesign by Raha Tabar